Belle Clayton (27/06/2023)

Crystallised Inspiration

In 2021, we interviewed Noushine Shahidzadeh in “The World of Crystals Around You!” about her area of expertise - crystallisation. As I listened to Noushine explain how science has heavily shaped her worldview, a relatable feeling washed over me. One of the beauties of studying this fascinating field is realising that it makes up every part of our being. The more you learn, the more you see that science is hiding in plain sight wherever you turn - from the bent molecules of hydrogen and oxygen in a glass of water to the device you are reading this on.

The episode made me realise that crystals are yet another phenomenon that silently pervades our daily lives, and one that has completely taken over Noushine’s! While others go on holidays to snap picture-perfect landmarks, she seeks out degrading buildings destroyed by crystals. In the supermarket, while most people see a powder that adds flavour to their food, Noushine sees a lattice of beautiful repeating structures that inspire her life’s work. The substance at hand is sodium chloride, the most abundant salt in the world.

Salt grains under a microscope.

Source: Alexander Klepnev, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Source: Alexander Klepnev, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the episode, Noushine enlightens us about the importance of crystals in numerous fields, including healthcare, agriculture, and the food industry, to name a few. One thing that particularly stood out to me was their influence in the art world, with salt having a huge impact on the longevity of art in all sorts of mediums. Salt-based reactions can result in corrosion and damage to artworks, causing havoc with their original colour and structure and completely changing their essence. Historically, salt has also been mistakenly applied to paintings as a preservation and cleaning material! Little did the previous generations know that their efforts to conserve would actually be the cause of their beloved objects’ demise.

This train of thought got me thinking: how else have crystals impacted the art world? And besides Noushine, who have they served as inspiration for? I did not have to search for long to see humans have long been captivated by the enchanting shapes and colours of crystals. Archeologists believe that we have given the minerals importance for the last 100,000 years, using them for medicine, music, spirituality, status, and fashion. This obsession has given birth to an array of exquisite jewellery, clothes, paintings, sculptures, and engravings.

One artist who has taken huge inspiration from crystallised media is Japanese born Motoi Yamamoto. His intricate, repeating patterns remind me of the similarly structured motifs inside each grain of salt he utilises. Unlike actual crystal structures, which can come together in seconds due to opposing charges, Yamamoto's crystallised art work takes anywhere from a few days to a few weeks.

Yamamoto’s popularity stems from the universal relatability of the themes in his work. Salt is vital for humans to consume; without it, our cells would stop functioning completely, and more importantly, our food would be bland. People throughout history have understood the immense importance of salt, with many civilisations being built upon it. For example, the mineral has played a vital role in the technological and political development of China over the past 2000 years through a salt tax.

Yamamoto prides his exhibitions on being transient, just as the visitor's time is with the pieces themselves. After the end date of his showcases, he collects the salt and places it into the ocean, returning the medium back into nature. Similarly to Noushine’s research, Yamatoo’s astounding labyrinths are a love letter to the mineral.

This train of thought got me thinking: how else have crystals impacted the art world? And besides Noushine, who have they served as inspiration for? I did not have to search for long to see humans have long been captivated by the enchanting shapes and colours of crystals. Archeologists believe that we have given the minerals importance for the last 100,000 years, using them for medicine, music, spirituality, status, and fashion. This obsession has given birth to an array of exquisite jewellery, clothes, paintings, sculptures, and engravings.

Stunning salt structures

One artist who has taken huge inspiration from crystallised media is Japanese born Motoi Yamamoto. His intricate, repeating patterns remind me of the similarly structured motifs inside each grain of salt he utilises. Unlike actual crystal structures, which can come together in seconds due to opposing charges, Yamamoto's crystallised art work takes anywhere from a few days to a few weeks.

Yamamoto’s popularity stems from the universal relatability of the themes in his work. Salt is vital for humans to consume; without it, our cells would stop functioning completely, and more importantly, our food would be bland. People throughout history have understood the immense importance of salt, with many civilisations being built upon it. For example, the mineral has played a vital role in the technological and political development of China over the past 2000 years through a salt tax.

Yamamoto prides his exhibitions on being transient, just as the visitor's time is with the pieces themselves. After the end date of his showcases, he collects the salt and places it into the ocean, returning the medium back into nature. Similarly to Noushine’s research, Yamatoo’s astounding labyrinths are a love letter to the mineral.

Photograph of Motoi Yamamoto’s Labyrinth installation.

Source: University of Charleston, Forces of Nature, 2006, The Post and Courier.

Source: University of Charleston, Forces of Nature, 2006, The Post and Courier.

Forever frozen in time

Another artist that sees salt as their muse is Alexis Arnold, who plays with the experience of light, space, and colour through geology. Many of her creations are crystallised sculptures of everyday objects that have been converted into sparkling frozen snapshots. Arnold’s works involve antique kitchen objects, crab shells, teddy bears, and bicycles. Though out of all the artist’s breathtaking pieces, my personal favourite is their book collection.

Arnold transforms books into geological specimens to juxtapose the materiality of books with their timeless context. After crystallisation, each exquisite book still holds its history of use and message hidden beneath its hard exterior. Scrolling through some of these chosen titles - including ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ ‘Mastering the Art of Beekeeping Vol. 2’ and the ‘San Francisco Phone Book’ - it feels like a personal look into the artist's consciousness. Arnold appears to have selected these novels because of their personal meaning or societal impact.

Arnold, Alexis. Treasures from the Map Room : A Journey through the Bodleian Collections. 2022. Book, borax, 11.25 x 17 x 11.5 inches.

Source: Alexis Arnold.

Source: Alexis Arnold.

Salty memories

In 1839, salt became a key player in revolutionising photographic prints. Scientist William Henry Fox Talbot - aka the modern father of photography - invented a direct, innovative method that allowed multiple copies of an image to be produced by a single negative. Their technique started with dipping a sheet of writing paper into a weak solution of humble table salt before instantly blotting it dry and brushing it with silver nitrate. These conditions create a chemical backdrop that is extremely light-sensitive, allowing for the projection of a negative to be printed onto it with the help of some UV rays. To stabilise the print, a strong salt bath is then recruited, and voila, a sharp image of your photograph full of detail is at your fingertips.

The light-fast speed of this technique made people nickname it “automatic photographic paper” and allowed printing the memories held in negatives to become a lot more accessible. Throughout the 19th century, salt printing was altered and improved, recruiting new chemicals to improve the stability, sharpness, and tone of the images it produced. To achieve this, photographers who dared to experiement added some interesting substances to the surface of printing paper at different stages of the process, including gold chloride, gelatin, starch, resins, albumen (egg white), beeswax, or shellac.

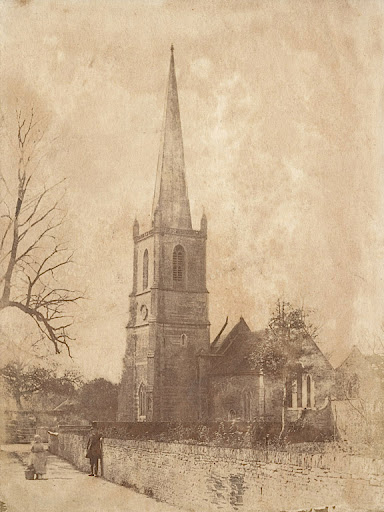

Left: Unknown. Saint Michael's Church, Winterbourne, England. April 1859. Salted paper print.

Source: Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC.

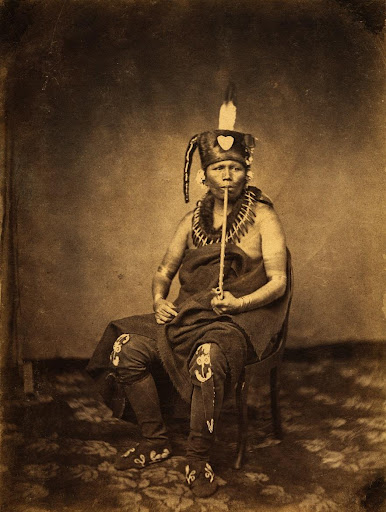

Right: Vannerson, Julian. Tá-ka-ko (Grey Fox), a chief of the Sacs and Foxes. 1858. Salted paper print, 19.9 x 15 cm.

Source: Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Source: Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC.

Right: Vannerson, Julian. Tá-ka-ko (Grey Fox), a chief of the Sacs and Foxes. 1858. Salted paper print, 19.9 x 15 cm.

Source: Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Some more gems

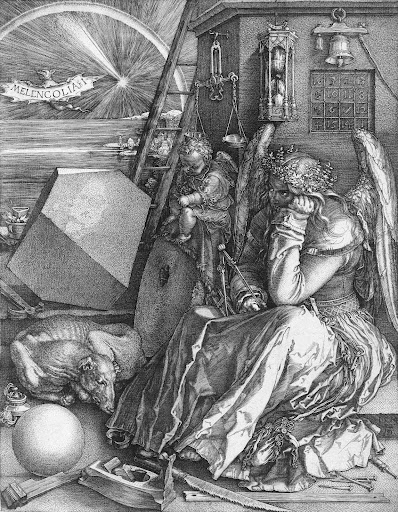

Another piece of art from the last few hundred years that draws inspiration from crystals, is Albrecht Dürer's engraving from 1514, ‘Melencolia I’. The artist employed an eye-catching geometric design to express the Renaissance artist's melancholy message. Dürer was clearly inspired by mathematics, with this engraving including a ‘magic square’ and other allusions to geometry.

One more example where the beauty of crystals has been translated to art is girih tilings, a set of five geometric titles that have been used for decoration on Islamic architecture for over 800 years. Some argue that these elaborate geometric designs take inspiration from quasicrystal structures, which continuously fill up space but lack certain kinds of symmetry.

Left: Dürer, Albrecht. Melencolia I. 1514. Copper plate engraving.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Right: Decoration of the Tuman Aqa complex in the Shah-i Zinda, Samarkand.

Source: Patrickringgenberg, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Right: Decoration of the Tuman Aqa complex in the Shah-i Zinda, Samarkand.

Source: Patrickringgenberg, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

A difference in perception

Ever since I listened to Noushine’s podcast episode, I can’t help but see the world of crystals around me differently. When I add salt to my bubbling pasta water, I now see structured lattices birthed from chaos that have served as an inspiration to many across the ages. I want to end by wishing Noushine all the best in her research. I hope she is successful in her quest to protect both priceless works of art and human health.

Want to hear more about Noushine’s research? Check out episode 7, titled ‘The World of Crystals Around You! ‘.