Belle Clayton (20/05/2023)

The Evolution of Democracy

In our episode titled “What Does the Democracy of the Future Look Like?” we talked to Ulle Endriss about his intriguing field of research. It seems many of our listeners found this topic enthralling as well, with this recording being our most played to date. In a time of constant political and social turmoil, this really comes as no surprise. Most of us have dreamed of a dystopian future where the unjust, outdated ways of our political system are a thing of the past.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Endriss' research aims to contribute towards this more ideal society, one that is fairer for all. But what does this future even look like? I don’t know about you, but at first thought I found it extremely difficult to imagine. To give us some inspiration, let’s have a brief look at the shape-shifting history of democracy.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Endriss' research aims to contribute towards this more ideal society, one that is fairer for all. But what does this future even look like? I don’t know about you, but at first thought I found it extremely difficult to imagine. To give us some inspiration, let’s have a brief look at the shape-shifting history of democracy.

The roots of democracy

People commonly consider the Ancient Greeks to have invented democracy, with the word literally coming from the Greek demokratia, however, this was no new idea. Most city states and empires across ancient, pre-colonial Africa and early Mesoamerican societies had been operating under some type of democratic system long before the Greeks entered the picture. Despite these societies not having written constitutions or holding elections, most people had some kind of say in their community.

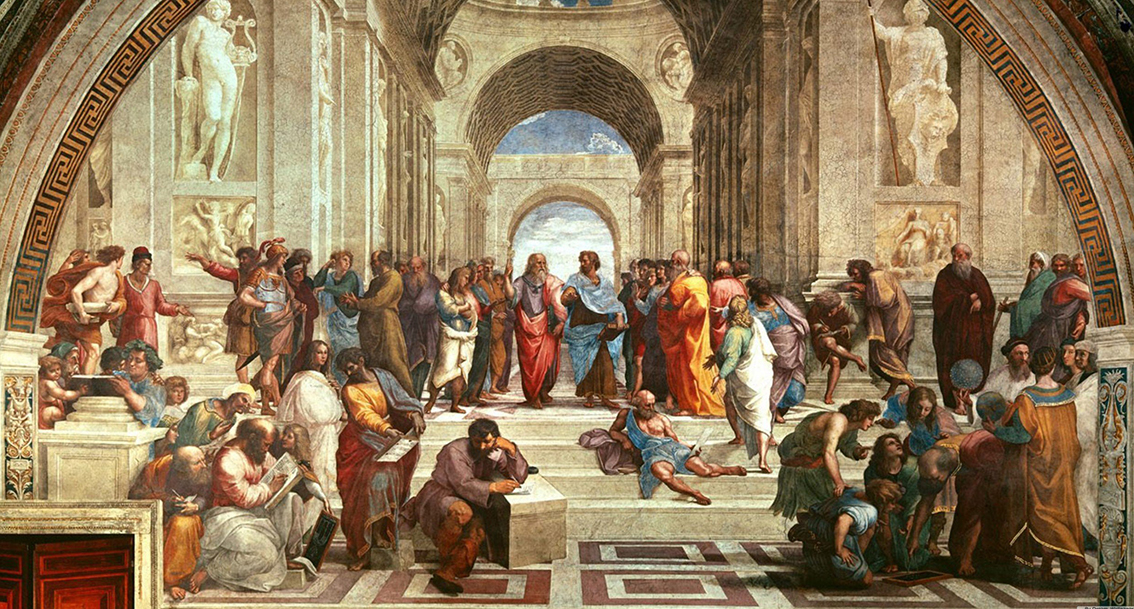

Around the fifth century B.C.E., democracy appeared in Athens, born out of the idea that citizens should have an active role in their land’s governance. Their version of democracy was the most complex system that had been thought up to that date, plus it encouraged debate and criticism of ideas. The people elected would be involved in all parts of society, including initiating legislation, political trials, organising and maintaining food supplies, financial issues, and more. The Ancient Greeks set up precautionary measures to ensure no single individual carried too much influence over one area of governance.

Although more progressive than the oligarchical and tyrannical rule of previous governments, this democracy was far from perfect. One of the system's biggest critics was Aristotle, a famous philosopher and polymath. He saw this political organisation as being too easy to manipulate, which was proven correct multiple times when the winners of elections were those who purchased popular support through monetary means (sound familiar?). This ancient version of democracy also only allowed “citizens'' of Athens to vote. This included free men born in the city aged over 18 and excluded around three-quarters of the population from inputting anything at all. The system was unjust and inhumane in many ways, including its punishment system and intensely militaristic nature. All in all, the needs of the masses were still largely not being met, with only a facade suggesting that they were.

Raphael. The School of Athens. 1509–1511. Fresco, 550 x 770 cm. Apostolic Palace, Vatican City.

Source: The Vatican.

Source: The Vatican.

The current state of democracy

In many ways, the democracies of today are still facing many of the same issues as 2000 years ago: with destructive foreign policy being played out, monetary corruption being rife, and examples of the needs of the few elite outweighing the many. However, it is clear that democracy has evolved to incorporate many positive changes.

The most important is that a larger proportion of society is now able to have their say with the vote. Although not every person living in each democratic country has the right to vote, it is undeniable that citizen participation has hugely increased. In turn, this rise in political involvement and growing principles of equality have also pushed many democratic societies to develop government welfare programmes. These financial aids have been put in place to assist people who may not be able to support themselves through work. This money is supposed to come from taxation which allows the redistribution of wealth from the richer members of society to the poorer ones.

So why is this ideal sounding system, where most of the population has the opportunity for their voice to be heard, failing so many of us?

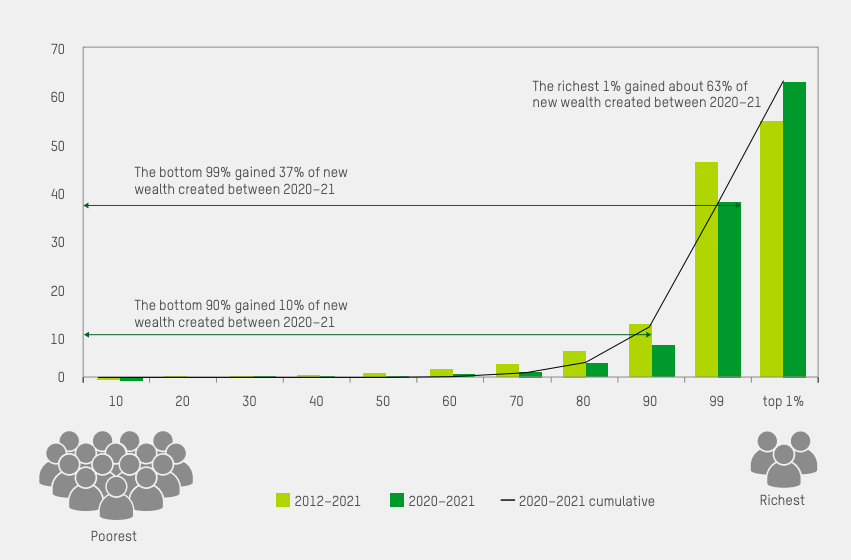

The face of this failure may take on a different shape depending on who you ask. However, no matter where you stand on the political spectrum, it is clear that the current system favours market profits and self-interest over transparent democracy, a.k.a. captialism. It is obvious that the richer members of society have a greater sway on policy than the poor, with governments commonly exchanging tax breaks and political influence for donations and business presence. Unrest is growing around the world in many democratic countries due to some of this practise’s inevitable outcomes; including environmental damage, inhumane treatment of workers, economic instability, and enormous wealth disparities that have led to class struggle. A recent study from Oxfam found that the richest 1% of the entire population extraordinary hoarded half of all new wealth created globally over the past few years.

Bar chart that show the share of new wealth gained between 2020-2021.

Source: Oxfam calculation based on Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report.

Source: Oxfam calculation based on Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report.

No matter where you look, no political system is perfect and needs to evolve. A general theme that can be spotted scross the globe is that a small percentage of top earners and elected officials hold a disproportionate amount of power and cannot be fully held to account. It seems as though the logical progression of democracy is pushing it closer towards its true form - a system that allows citizens to have a meaningful say rather than the cloak of one.

Technology to the rescue?

As Endriss explains in the episode, Amsterdam’s buurtbudgetten are a small step in the right direction. This initiative has allowed people to have a direct say on how their own tax money is being spent - because who knows what resources a neighbourhood needs better than the people actually living there?! Whether that be the organisation of more community gatherings to decrease loneliness, food banks, educational classes, libraries, or green spaces, these ideas really have the potential to increase the everyday person’s quality of life. In this instance, it is clear how technology can aid democracy, making both urban policy-making and participatory democracy more accessible.

Gemeente Amsterdam is not the first governmental body to use algorithms for these reasons. Madrid City Council has been utilising the programme Decide Madrid since 2015 as a way to try and improve public participation in local government matters in the midst of austerity and corruption scandals. Here, citizens have the chance to have their say on how the public budget (100 million Euros) is spent and to promote transparency in governmental practices. vTaiwan is another interesting example of digital democracy, with over 80% of the cases put forward to the public via the programme leading to decisive government action. One of these is the regulation of Uber in the country to ensure fair competition with local taxi services, providing job security to individuals in the trade rather than profit for a multi-billion dollar company.

Screenshot of the mass deliberation on ridesharing as part of the vTaiwan scheme.

Source: Nesta.

Source: Nesta.

As these programmes have become readily available, many global activists, researchers, and government officials have called for an increase in open-source digital platforms for facilitating decisions surrounding development and legislation; however, we should still remain somewhat sceptical. Technology has influenced the global political landscape in profound ways, mostly making it a whole lot more confusing! Using algorithms for democratic means sounds great in theory, though academics commonly find that these programmes surface with some sort of bias that leaves the most marginalised communities disadvantaged - whether that be routed in class, gender, or race. Further work is needed to combat these biases before we let algorithms run free through our political landscapes.

Time will tell

If you’re still not feeling entirely certain of a promised fairer future, that’s okay, me too. With that said, it's important to keep in mind that we have indeed seen positive systemic changes since the birth of our current political system. The path to progression was never going to be linear, though it’s up to working people to mobilise towards it. It is clear that the younger generations are politically energised and that an increasing percentage of the population is seeing the cracks in our current way of doing things. Maybe this is just the environment needed for change... Hopefully, (with the help of AI or not) we will see a wider dispersion of power with an increase in public participation, whether that be via citizen assemblies or accessible online platforms.

Interested in hearing more about Ulle’s fascinating research? Check out episode 3 of Talk That Science, titled “What Does the Democracy of the Future Look Like?” to hear more about the computational process behind collective decision making.

Time will tell

If you’re still not feeling entirely certain of a promised fairer future, that’s okay, me too. With that said, it's important to keep in mind that we have indeed seen positive systemic changes since the birth of our current political system. The path to progression was never going to be linear, though it’s up to working people to mobilise towards it. It is clear that the younger generations are politically energised and that an increasing percentage of the population is seeing the cracks in our current way of doing things. Maybe this is just the environment needed for change... Hopefully, (with the help of AI or not) we will see a wider dispersion of power with an increase in public participation, whether that be via citizen assemblies or accessible online platforms.

Interested in hearing more about Ulle’s fascinating research? Check out episode 3 of Talk That Science, titled “What Does the Democracy of the Future Look Like?” to hear more about the computational process behind collective decision making.